“Cells from a woolly mammoth that died 28,000 years ago have begun to show signs of biological (activity).”

The 28,000-year-old Woolly Mammoth, ‘Yuka’ were found in Siberian Permafrost. The 28,000-year-old Woolly mammoth was dug out of Siberian permafrost in 2011, now scientists have found that its DNA is partially intact.

“Yuka” is the best preserved Woolly Mammoth carcass ever found. Eight years ago it was discovered by local Siberian tusk hunters in 2010. They turned Yuka to the local scientists, who made an initial assessment of the carcass in 2012.

Yuka was an impressively well-preserved woolly mammoth, it was found along the Oyogos Yar coast in the region of Laptev Sea. Yuka is a juvenile female natural mummy that was found near and named after the village of Yukagir, whose people discovered it. After its discovery, Yuka spent two years stored and preserved in a natural refrigerator, the local permafrost in Yukagir.

An analysis of the teeth and tusks determined Yuka to be approximately 6–8 years old when it died. Although it is presumed that Yuka had most likely been attacked by lions or other predators, evidence that the predators had killed the mammoth was not found

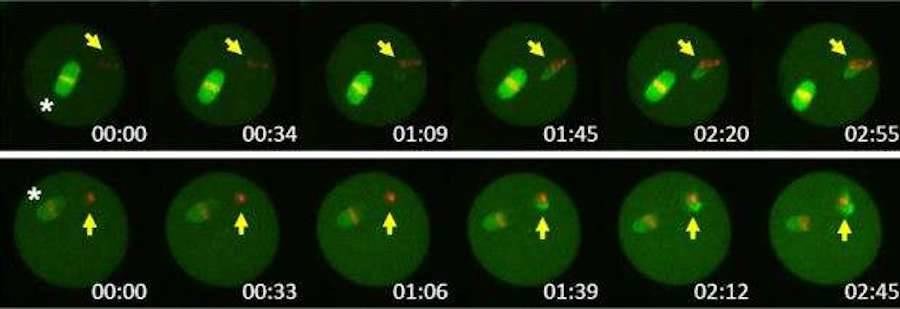

Since then scientists have been eagerly studying Yuka in an attempt to learn how viable its biological materials still are. Writing in the journal; Scientific Reports, scientists from the Kindai University of Japan have documents mammoth nuclei showing “signs of biological activity” after being transplanted into mouse oocyte cells.

“Here we recovered the less-damaged nucleus-like structures from the remains and visualized their dynamics in living mouse oocytes after nuclear transfer.” The proteomic analysis demonstrated the presence of nuclear components in the remains. The nucleus like structures found in the tissue were histone – and lamin positive by immunostaining.

The study’s abstract reveals, “In the reconstructed oocytes, the mammoth nuclei showed the spindle assembly, histone incorporation, and partial nuclear formation; however, the full activation of nuclei for cleavage was not confirmed. DNA damage levels, which varied among the nuclei, were comparable to those of frozen-thawed mouse sperm and were reduced in some reconstructed oocytes. Our work provides a platform to evaluate the biological activities of nuclei in extinct animal species.”

The research details how the well-preserved woolly mammoth has begun to show some activity. “This suggests that, despite the years that have passed, cell activity can still happen and parts of it can be created… Until now many studies have focused on analyzing fossil DNA and not whether they still function.” Kel Miyamoto, a member of the team that conducted the work said.

Radiocarbon dating suggested that the Yuka mammoth was 28,140 (±230) years old. The process to find out whether the mammoth DNA could still function wasn’t easy. The researchers began by taking bone marrow and muscle tissue from the animal’s leg. These were then for the presence of undamaged nucleus-like structures, which were extracted and then transferred into living mouse oocytes, cells found in ovaries that can undergo genetic division to form an egg cell.

After the nuclear transfer, the mouse proteins were added, which revealed that some of the mammoth;’s cell started to show signs of nuclear reconstitution. This gave us a hint that ancient mammoth remains might still possess partially active nuclei.

Five of the cells even displayed stages of activity that occur immediately before the cell division. The study maintains that “the full activation of nuclei for cleavage was not confirmed.”

Kei Miyamoto told Nikkei Asian review that this research was a “significant step towards bringing mammoths back from the dead.” However, these are still the early day, we have to study forward to the stage of cell division but still, were far from recreating a mammoth.

Kindai University’s team is collaborating with a Russian institution on the work using a cloning technology called somatic cell nuclear transfer.

However, there were various levels of DNA damage done, which the researchers termed, “were comparable to those of frozen-thawed mouse sperm and were reduced in some reconstructed oocytes.” While the damaged elements on the cells are not enough for bringing the mammoth back to life.

Most mammoths died out between 14,000 and 10,000 years ago, towards the end of the last glacial period. But one population managed to survive on Wrangel Island in the Arctic Ocean until 4,000 years ago, which means they lasted hundreds of years after the construction of the Great Pyramid of Giza.

Miyamoto believes that we are very far from recreating a mammoth, but some researchers are trying to bring the mammoth back with the use of gene addition, including the controversial CRISPR gene-editing tool.

Harvard and MIT Geneticist and co-founder of CRISPR, George Church is the head of the Harvard Woolly Mammoth Revival team, a project that is trying to introduce mammoth genes into the Asian elephant for conservation purposes.

“The elephants that lived in the past — and elephants possibly in the future — knocked down trees and allowed the cold air to hit the ground and keep the cold in the winter, and they helped the grass grow and reflect the sunlight in the summer,”

“Those two factors combined could result in a huge cooling of the sol and a rich ecosystem,” Miyamoto’s team focuses on reaching the stage of cell division, and so far the results are promising.