Mount Everest, the tallest mountain in the world, has claimed the lives of over 300 daring adventurers since the first confirmed summit in 1953 by Sir Edmund Hillary and Tenzing Norgay. Of these fallen climbers, over 200 corpses remain scattered across Everest’s hostile landscape, serving as ghostly reminders of the risks involved in attempting to scale the 29,032 ft (8,849 m) peak.

The Treacherous Death Zone

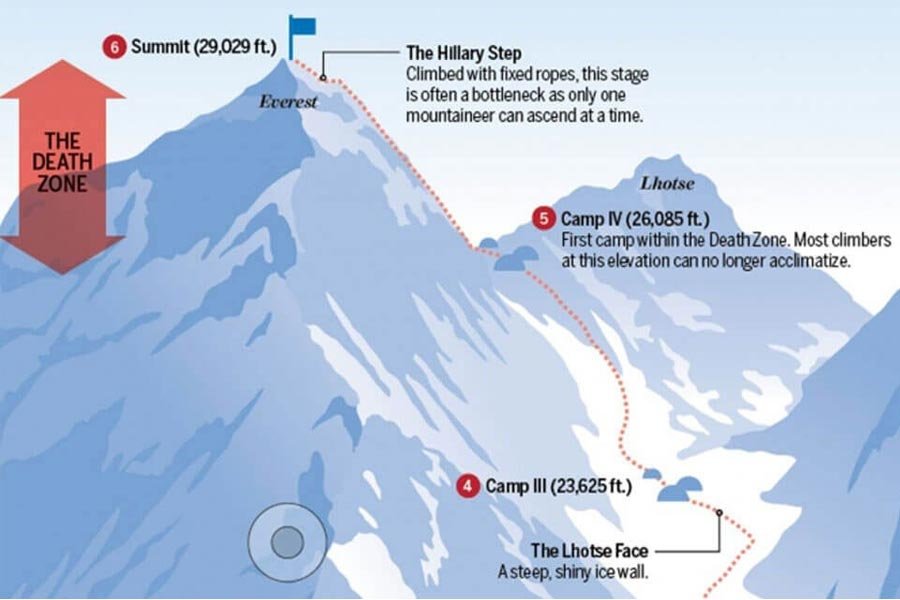

The primary danger zone on Everest lies between 26,247 ft (8,000 m) and the summit, an area mountaineers have grimly dubbed the “death zone.” At this altitude, oxygen levels drop to around 30% of those at sea level, making simple tasks like walking extremely arduous. Climbers’ brains and lungs slowly starve for oxygen, inducing exhaustion, confusion, and distress.

Prolonged exposure and physical exertion in the death zone put climbers at high risk of developing deadly conditions like cerebral edema (fluid in the brain), pulmonary edema (fluid in the lungs), blood clots, snow blindness, frostbite, and hypothermia. Sudden cardiac death is also common. Without supplementary oxygen, even the fittest climbers can only spend a maximum of 48 hours in the death zone before deteriorating health forces descent or death.

Bodies That Haunt Everest’s Slopes

Over the decades, scores of climbers have collapsed and died in Everest’s death zone, either from exhaustion or extreme weather conditions. Given the challenges and dangers involved in retrieving bodies from such high altitudes, many have been left where they perished, serving as haunting landmarks for future expeditions.

Some of the most well-known corpses include:

“Green Boots”

This climber’s brightly-coloured footwear identified him when he died in a small enclave dubbed “Green Boots Cave” in 1996. Believed to be Tsewang Paljor, an Indian climber who perished in the 1996 Mount Everest disaster, Green Boots continues to lie where he took his last breaths.

David Sharp

In 2006, British climber David Sharp became separated from his group and later died of exposure and exhaustion in a small cave during his descent. Over 40 climbers passed Sharp as he lay dying, drawing criticism for failing to help. His body remains in the cave, known as “Green Boots Cave.”

Hannelore Schmatz

In 1979, German climber Hannelore Schmatz became the first woman to perish on Mount Everest after collapsing from exhaustion just 330 feet (100 m) short of Camp 4 on the south summit route. Her body has become a familiar marker for climbers ascending the southern route.

George Mallory

Mallory’s frozen corpse was discovered in 1999, fueling debate about whether he and climbing partner Andrew Irvine had first summited Everest 75 years earlier in 1924. Mallory had attempted Everest three times in the 1920s before disappearing on his last try.

Francys Arsentiev

Francys Arsentiev, the first American woman to summit Everest without supplementary oxygen, died during her descent in 1998. Her husband died trying to save her. Other climbers later found Francys’ body, now known as “Sleeping Beauty,” tied to rope to prevent it sliding downhill.

Roberto Manni

In 2012, Roberto Manni of Italy collapsed and died near the Balcony area after successfully reaching Everest’s summit. His corpse, seated in the snow and seemingly staring into the distance, unsettled passersby who glimpsed his body.

Why Are Bodies Left Behind?

Given the hostile conditions and dangerous terrain on Everest, removal or retrieval of bodies poses a tremendous risk, beyond the means of most climbers physically weakened by low oxygen levels. Teams specializing in retrieval require significant funding and resources. As such, expeditions generally accept that casualties will remain where they fall on Everest’s slopes.

Additionally, climbers often lack the energy or means to move bodies in the death zone, struggling just to save themselves. Jonathan Krakauer wrote in Into Thin Air of stepping over a dying woman pleading for help on his own Everest descent. Survival instinct takes over in the death zone’s grip.

Even for climbers further down the mountain, carrying a body at over 20,000 ft (6,000 m) is an impossible feat. The missing oxygen alone makes even simple movements exhausting.

Climbing Everest Alongside Death

For climbers, the Everest experience often includes brushes with death and encounters with bodies both fresh and decades old. Author Jon Krakauer describes a chilling scene in Into Thin Air of passing “an Indian climber who had frozen solid while attempting to descend the fixed ropes.” A common macabre sight involves corpses emerging from the ice as climate change melts glaciers near Everest’s summit.

During bids for the summit, living climbers frequently face moral dilemmas when coming across others in distress or collapsing. Explorers may lack the energy themselves to conduct a rescue. Hallucinations from oxygen deprivation present an added variable in decision-making and reliability when helping others.

While witnessing death first-hand, Everest climbers become intimately familiar with their own mortality. Veteran climbers strongly caution others to resist the temptation of “summit fever”: becoming so fixated on reaching the top that one ignores signs of deterioration or declining weather until it’s too late to turn back. This obsession with the summit causes many mountaineering tragedies.

On Everest, life-and-death decisions must constantly be made under physical and mental duress. Climbers realize from expired corpses along the route that errors in judgement carry severe consequences. Teams prepare accordingly, bringing supplementary oxygen, adjusting for altitude sickness, and establishing protocols for when to turn back, though outcomes remain uncertain when challenging the mighty peak.

Debates Around Notable Bodies

The discovery of well-known deceased climbers has frequently sparked debate within mountaineering circles.

George Mallory – Mallory and climbing partner Sandy Irvine’s disappearance on Everest in 1924 left lingering questions about whether they could have summited 29 years before Hillary, decades before the first confirmed ascent. The finding of Mallory’s body in 1999 preserved his clothing and accessories, which showed the climbers were prepared to possibly summit. Kodak film rolls found on Mallory’s body were undeveloped, leaving the mystery unresolved.

David Sharp – Sharp’s death raised arguments about whether exhausted climbers still have a moral duty to help others in peril near the summit, perhaps fatally compromising their descent. Over 40 passersby declined to help Sharp as he lay dying in 2006, though some reported trying to administer oxygen. Others stated that efforts would have been futile or cost them their lives. Sharp’s death brought the “code of the mountains” into question.

Hannelore Schmatz – Schmatz’s demise just above Camp 4 in 1979 reinforced the dangers of exhaustion on Everest, especially when every last ounce of energy has been exerted toward the summit. Some cited inadequate support from Sherpas and fellow climbers in contributing to her collapse. The proximity of her death to base camp showed no area on Everest is truly safe.

Anatoli Boukreev – Following the 1996 Everest disaster, Boukreev received criticism for descending ahead of clients after summiting. But his absence was linked by some analysts to better survival rates for his group versus other expeditions impacted by the storm. The morality of guides looking after their own safety versus protecting wards was debated after this Everest tragedy.

The Lack of Burials and Missing Persons on Everest – It is challenging to accurately identify recovered bodies or match them to missing climbers. Over the decades, detailed records were not kept of those who perished but were never recovered. Recent DNA analysis has begun to provide names for previously anonymous corpses. But a majority of bodies remain unidentified mysteries, adding to Everest’s aura of otherworldliness.

The Costs and Ethics Around Everest Body Retrieval

Recovering bodies from the death zone and upper slopes carries tremendous risk and cost. Some argue the resources would be better spent elsewhere rather than endangering more lives. Others believe climbers have a moral obligation to bring the fallen home regardless of difficulty. This debate around retrieval ethics persists each season.

Changes in Body Preservation Over Time

Newer bodies tend to be well-preserved by the cold. Older remains become more decayed and skeletal as years go by, sometimes shifting or emerging from melting glaciers. Their varying states provide insight into Everest’s volatile landscape and climate changes over the decades.

Religious Aspects Around Death on Everest

Some sherpas refuse to touch or move bodies, fearing spiritual consequences. Beliefs around death and sacredness lead many to advocate leaving the fallen undisturbed. These religious views further complicate body retrieval on Everest.

In recent years, recovery specialists have safely retrieved and identified bodies when possible, showing increased mountaineering respect for the dead. For example, expeditions returned Francys Arsentiev and Hannelore Schmatz to be buried at home. These efforts demonstrate greater care for paying final respects.

While Everest’s importance abides, many corpses scattered along its slopes serve as sobering reminders of the grim toll climbing the world’s tallest peak can take. For decades to come, glaciers will gradually surrender more fallen explorers. As climate change forces the mountain’s hand, what new tales might these frozen bodies reveal in their final resting places?

The retrieval of bodies from Everest remains exceedingly difficult due to adverse weather conditions, treacherous terrain, and oxygen deprivation. The hostile environment of Everest makes it nearly impossible to safely recover bodies once a climber has died. Weather can quickly shift from clear to blizzard conditions, with fierce winds and brutally cold temperatures that threaten survival. The knife-edge ridges and slippery, unstable surfaces climbers must traverse to even reach bodies also pose mortal dangers. At high altitudes where corpses lay, the lack of oxygen clouds judgement and rapidly accelerates exhaustion. For these reasons, most bodies must remain where they perished. The dead of Everest reside in a harsh domain that resists all efforts to reclaim them.

Read More –